Some people are born with two colors in the same eye, or central heterochromia, due to a genetic mutation affecting melanin production. Others can develop it due to an injury or health condition.

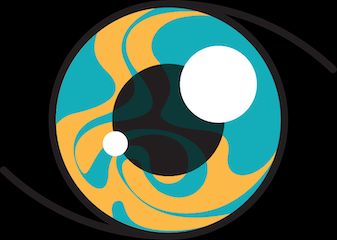

Rather than have one distinct eye color, people with central heterochromia have a different color near the border of their pupils.

A person with this condition may have a shade of gold around the border of their pupil in the center of their iris, with the rest of their iris another color.

It is usually harmless and does not require treatment. But, it can sometimes be a symptom of an underlying health condition.

Central heterochromia describes the location of the pigment change in heterochromia, a term for having different eye colors. There are two forms of heterochromia:

- Congenital heterochromia: Some people are born with this type of central heterochromia or develop it shortly after birth.

- Acquired heterochromia: People who develop central heterochromia later in life due to an eye or health condition have this form.

Other types of heterochromia include:

- Complete heterochromia: People with complete heterochromia have eyes that are completely different colors. For example, one eye may be green, and the other may be brown, blue, or another color.

- Segmental heterochromia: This type of heterochromia is similar to central heterochromia. But instead of affecting the area around the pupil, segmental heterochromia affects a larger portion of the iris. It can occur in one or both eyes.

Read on to learn how this condition differs from other types of heterochromia, what may cause it, and how it’s treated.

Central heterochromia causes a ring of one different color around the border of your pupil.

If you have hazel eyes, it means your eyes contain colors that may appear different depending on the lighting. But this color is dispersed throughout the whole iris rather than just around the pupil.

To understand possible causes of central heterochromia and heterochromia in general, you need to look at the relationship between melanin and eye color. Melanin is a pigment that gives human skin and hair their color. A person with fair skin has less melanin than someone with dark skin.

Melanin also determines eye color. People with less pigment in their eyes have a lighter eye color than someone with more pigment. If you have heterochromia, the amount of melanin in your eyes varies. This variation causes different colors in different parts of your eye.

Congenital central heterochromia

Congenital heterochromia often occurs sporadically at birth due to a genetic mutation affecting melanin production in the eye.

It can appear in someone with no family history of heterochromia. It’s often a benign condition not caused by an eye disease. It does not usually affect vision, so it requires no treatment or diagnosis. However, in some cases, it may be a symptom of a health condition. This can include:

- Horner syndrome

- Sturge-Weber syndrome

- Waardenburg syndrome

- Piebaldism

- Hirschsprung disease

- Bloch-Sulzberger syndrome

- von Recklinghausen disease

- Bourneville disease

- Parry-Romberg syndrome

Acquired central heterochromia

Some people develop heterochromia later in life, however. This is known as acquired heterochromia, and it may occur from an underlying condition such as:

- eye injury

- eye inflammation

- bleeding in the eye

- iris nevi

- acquired Horner’s syndrome

- type 2 diabetes

- pigment dispersion syndrome (pigment released into the eye)

- certain medications for glaucoma

- eye surgery

Congenital heterochromia typically does not require diagnosis or treatment.

However, any change in eye color that occurs later in life should be examined by a doctor or ophthalmologist, a specialist in eye health.

Your doctor may complete a comprehensive eye examination to check for abnormalities. This includes a visual test and examination of your pupils, peripheral vision, eye pressure, and optic nerve. Your doctor may also suggest optical coherence tomography (OCT), a noninvasive imaging test that creates cross-sectional pictures of your retina.

Treatment for acquired heterochromia depends on the underlying cause of the condition.

No treatment is necessary when a visual exam or imaging test finds no underlying cause.

There isn’t specific prevalence information on heterochromia that appears near the border of the pupils.

But heterochromia, in general, is rare. It has an estimated prevalence of

Heterochromia may be a rare condition, but it’s typically benign.

It doesn’t usually affect vision or cause any health complications. However, when heterochromia occurs later in life, it may be a symptom of an underlying condition. If you develop changes in your eye color, shape, or vision, it is best to seek medical attention for a possible diagnosis and treatment options.