Black people are dying. And not just at the hands of police and neighborhood vigilantes, but also in the hospital beds where they should be appropriately cared for.

This goes for Black Americans in general, who often face implicit bias from clinicians — this happens even when those clinicians don’t have explicitly malicious intentions. This is wrong, and it must change.

According to the American Bar Association, “Black people simply are not receiving the same quality of healthcare that their white counterparts receive.”

This is most apparent in the case of Black maternal health, where preventable deaths occur due to these racial biases.

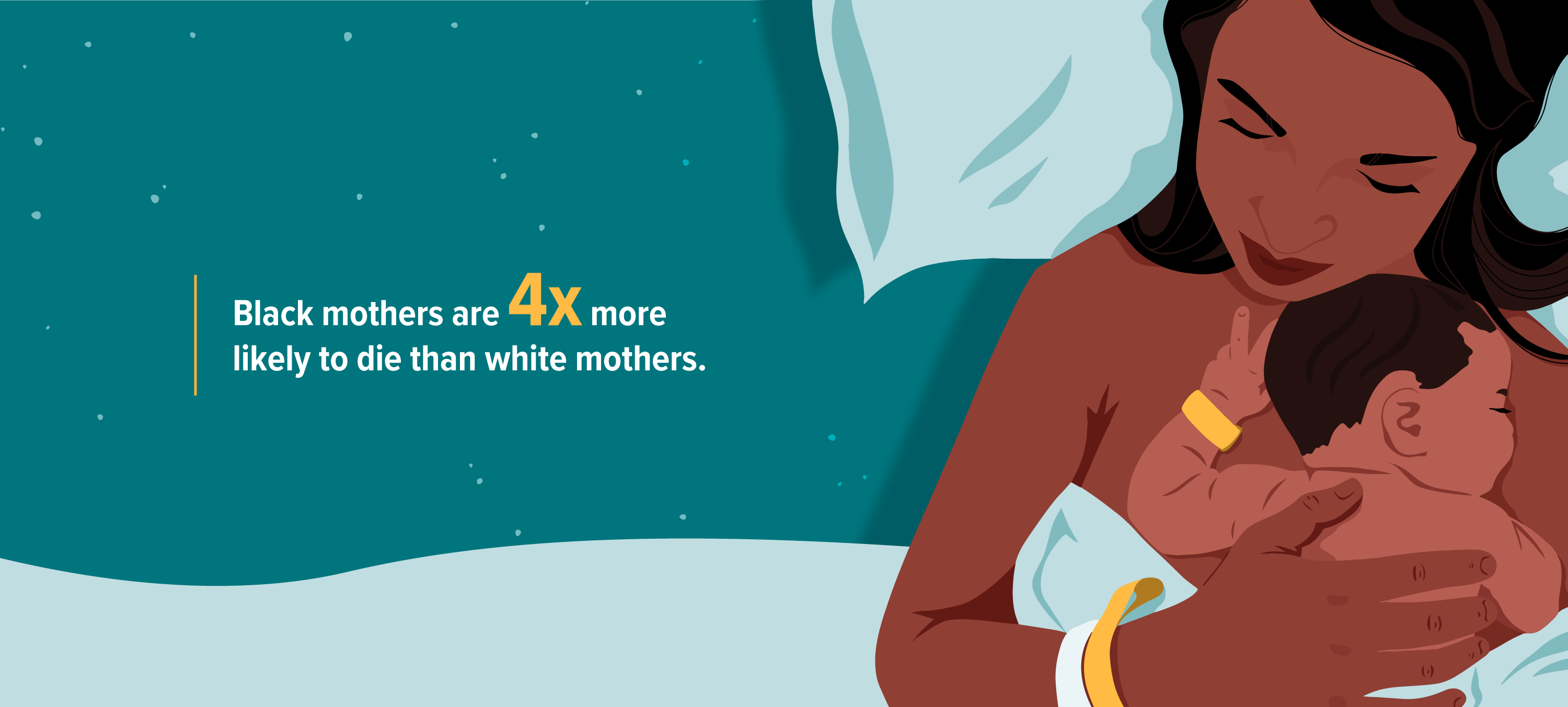

Black maternal death rates

Per the Harvard T.H. Chan Public School of Health, the

If you are alarmed by this statistic, it’s for good reason. The United States continues to be the richest country in the world, yet Black women face startling

And in some areas, like New York City, “Black mothers are [currently] 12 times more likely to die than white mothers,” according to Yael Offer, a St. Barnabas Hospital nurse and midwife, in a 2018 interview with New York’s News 12.

Just 15 years ago, this disparity was smaller — but still disappointing — at seven times higher. Researchers attribute this to drastically improved maternal healthcare for white women, but not for women who are Black.

Illustrations by Alyssa Kiefer

Biased health care

We are in an era where centuries of conflict and systemic racism are coming to a head, and it’s clear that the healthcare industry is failing Black women in tragic and fatal ways.

Dayna Bowen Matthews, author of “Just Medicine: A Cure for Racial Inequality in American Healthcare,” was quoted in an American Bar Association article stating that, “When physicians were given the Implicit Association Test (IAT) — a test that purports to measure test takers’ implicit biases by asking them to link images of black and white faces with pleasant and unpleasant words under intense time constraints — they tend to associate white faces and pleasant words (and vice versa) more easily than black faces and pleasant words (and vice versa).”

Matthews’ findings further illuminate that it’s not that white physicians are purposely trying to harm Black patients, but that patients face worse outcomes due to biases — ones their healthcare providers don’t even realize they have.

As with any phenomenon involving systemic inequalities, it’s not as simple as pure neglect of Black women once they conceive.

The saddening Black maternal health statistics are preceded by a deafening neglect of the physiological needs of Black people since birth, and this neglect leads to conditions that must be closely monitored throughout pregnancy.

According to Dr. Staci Tanouye, an alumna of the Mayo Clinic and one of TikTok’s most prominent OB-GYNs, “Black women do have higher risks for comorbidities such as uterine fibroids, which can increase [the] risk for things like preterm labor and postpartum hemorrhage. In addition, [Black women] have higher risks for chronic hypertension and diabetes, as well as pregnancy-related hypertensive disorders [like] preeclampsia [and] gestational diabetes.”

Why? These risks cannot be simply explained by genetic differences. Instead, these differences exist largely because of the

Dr. Tanouye is clear in her assertion that “these differences still do not account for the significant disparity in Black maternal deaths. In fact, even when corrected for, it doesn’t narrow the disparity by very much.”

While it would be deceptive to purposely exclude the physiological risks Black women face, these risks do not nearly add up to the jarring disparity between Black and white maternal deaths.

Navigating a flawed healthcare system

It’s obvious that the system — and the way we reverse learned racial biases— need quite a bit of work to improve inequities, but there are ways Black women can advocate for themselves.

Dr. Tanouye explains, “It is important for pregnant women to be particularly in tune with their bodies and symptoms. Specifically, watching for development of any new symptoms, especially in the third trimester, such as headache, nausea, swelling, visual changes, abdominal pain or cramping, bleeding, fetal movements, or just generally feeling unwell.”

Of course, it’s not as simple as just telling expectant mothers to know what to look out for. There have been Black women who have known something was wrong but have been disrespected by a clinician who didn’t make them feel heard.

That’s why Dr. Tanouye suggests that, “The best thing [Black mothers] can do is find a provider they are comfortable with.” She adds, “In an ideal world this is someone that they have already built a relationship and trust with over previous years. But we all know this is not usually possible or realistic.”

So, what should Black women do when they don’t have an existing provider?

As Dr. Tanouye explains, “Representation matters.” Sometimes the best option is to seek out a physician they relate to. “It is OK to seek out a provider who not only shares your values but maybe even shares a similar cultural background,” she asserts.

Black maternal health care can’t improve until Black healthcare improves as a whole

Failures in regard to Black maternal health serve as a microcosm of medical injustices against Black people across the medical landscape.

It’s important to note that change needs to be made not only in relation to maternal health, but in relation to how all Black patients feel when being treated by a healthcare provider — particularly when it’s not possible to choose your provider, as acknowledged by Dr. Tanouye.

I had a personal experience with this in 2018. I woke up one morning with intense stomach pain.

While standing in the shower, I felt a wave of nausea unlike anything I’d ever felt before. At that moment, I trusted my gut — literally. I had my husband rush me to urgent care, where my temperature was taken (I clocked in around 98°F, and I was asked if I had vomited yet [no]).

Based on those two factors alone, the urgent care physician tried to send me away, disregarding my explanation that fevers were atypical for me and that 98°F was high in my case because my temperature is typically around 96°F.

I also informed him that vomiting wasn’t normal for me. I’ve only done so a handful of times in two decades. I pleaded and pleaded for a CT scan, and he told me it was impossible to have appendicitis and that I should just go home.

But I would not cower. I would not take no for an answer. I was determined to advocate for my rights, because Black pain — both physical and emotional — has been disregarded for far too long.

I insisted that the physician order a CT scan so incessantly that I finally persuaded him to call my insurance company for authorization. He snarkily informed me, however, that I would likely be waiting an hour or more for my results since I was not sick and other patients were in actual need of care.

I was wheeled to my CT scan, and after being brought back to the examination room, I writhed in agony as my husband tried to entertain me by playing an episode of “Bob’s Burgers” on his phone.

Less than 10 minutes later, the physician rushed in. He frantically (albeit, unapologetically) informed me that I had severe appendicitis and needed to get to the hospital immediately and that they’d already informed the emergency room to schedule me for surgery.

The details after that are less important than the implications. I did not have the slow buildup to unbearable pain that many people with appendicitis experience. I did not run a fever. I did not vomit. I simply woke up that morning knowing that something was wrong.

And as I was being briefed by my surgeon and anesthesiologist, I was informed that my appendicitis, which unfolded in a matter of just hours, was so severe that I was less than a half-hour away from rupture. With rupture comes sepsis. And with sepsis comes the potential for disease, and, in far too many cases, death.

I still shudder remembering that had I not been persistent and just gone home as the urgent care doctor insisted, I might not be reporting about this right now.

Neglect of Black patients dates back to slave-era groupthink

My case is nothing new. There is a sinister history regarding how Black people have been treated in regard to healthcare that can be traced to the 19th century and earlier.

A study from The Journal of Medical Humanities details the infamous origin of the notion that Black people have less of a pain threshold than white people. It’s hard to grasp that fact, but sadly it’s true.

Researcher Joanna Bourke reports, “Slaves, ‘savages,’ and dark-skinned people generally were depicted as possessing a limited capacity to truly feel, a biological ‘fact’ that conveniently diminished any culpability amongst their so-called superiors for any acts of abuse inflicted on them.”

This slave master notion became a post-slavery notion, and this post-slavery notion has remained implicit, generation after generation.

Following the Emancipation Proclamation,

In response to her research regarding Vogt and the history of diminishing the pain of Black Americans, Bourke posits that it was thought that “African-Americans ‘cowered’ in silent tenacity, not because of any enlightened custom or educated sensibility, but simply because of a physiological disposition.”

Over time, the insidious notions and biases that have persisted in history have resulted in the awful Black maternal outcomes still being faced in America.

I think back to how terrified I was as the surgeon explained the severity of my appendicitis. My heart breaks thinking of how that terror must be infinitely more so when you’re worrying about the health of not only yourself, but [also] the child you are so lovingly carrying.

Black mothers aren’t taken seriously

Black maternal health is an illumination of a deeply flawed healthcare system, and it’s a shame that expectant mothers must undergo so much emotional labor — before the physical one even takes place — to be heard.

Kristen Z., an expectant mother in the Midwest, expressed deep frustration with the healthcare system after experiencing a miscarriage last year. “It was the most devastating experience of my life,” says Kristen, “and every step of the way I felt ignored.”

Kristen lives in a small town that, in her words, “is the farthest thing from diverse.” But while Kristen says she’s experienced situations throughout her life where she felt as if a healthcare provider wasn’t taking her seriously due to her being Black, nothing tops the pain of her miscarriage.

“It all happened so fast. I called my doctor because I was experiencing light bleeding, and he reassured me that it was just spotting and that it’s an incredibly common occurrence. In my heart I felt something was off, but I thought it was my head overthinking things and me just being paranoid about it being my first pregnancy,” she explains. The next morning, Kristen miscarried.

“I still get angry with myself sometimes for not trusting my gut. At the time of my miscarriage, I had recently changed doctors due to my health insurance changing,” Kristen says. “I didn’t want to be a problematic new patient or ruffle feathers.”

Kristen learned from that experience, however, and “quickly researched a new doctor after coping with my miscarriage.” She is proud to say that her current physician is an openly intersectional physician who doesn’t mind her “excessive hypochondria” and makes her feel safe expressing her concerns.

Kristen admits that she’s timid, saying “I should have spoken up. I know I should have. I still regret not being louder with my concerns, like I said. But I shouldn’t have to be this firm assertive person just to feel heard. It’s simply not me and never will be.”

Speak up — to a physician who listens

Anne C., a 50-year-old Black mother of three from upstate New York, has spent decades ensuring she receives proper medical care.

In the context of maternity, over the span of 17 years, she birthed three children with the help of three different OB–GYNs — and she largely experienced positive care. However, she attributes this to a common theme: the need to loudly advocate for herself.

When asking Anne whether or not she’d ever experienced poor or neglectful care during her pregnancies, she answered with a resounding “No.”

As an empowered Black woman, she is well aware that sometimes we are the only ones who truly have our backs. “You’re either going to listen to me, or I’m going to go somewhere else,” she says in regard to how she asserts herself to medical providers.

But for many Black women, the maternal journey isn’t such smooth sailing. Not everyone has the ability to switch to a different healthcare provider, particularly in the case of an emergency. Not every woman feels comfortable speaking up. Not every woman trusts their intuition, instead, second-guessing themselves.

Not every woman realizes that doctors can be biased, stubborn, and of course, fallible. Doctors may be reluctant to listen to patients, and patients may be reluctant to speak up. And even when Black mothers do speak up, as illustrated by modern statistics and tragedies, they sometimes fall victim to physician obliviousness, arrogance, and error.

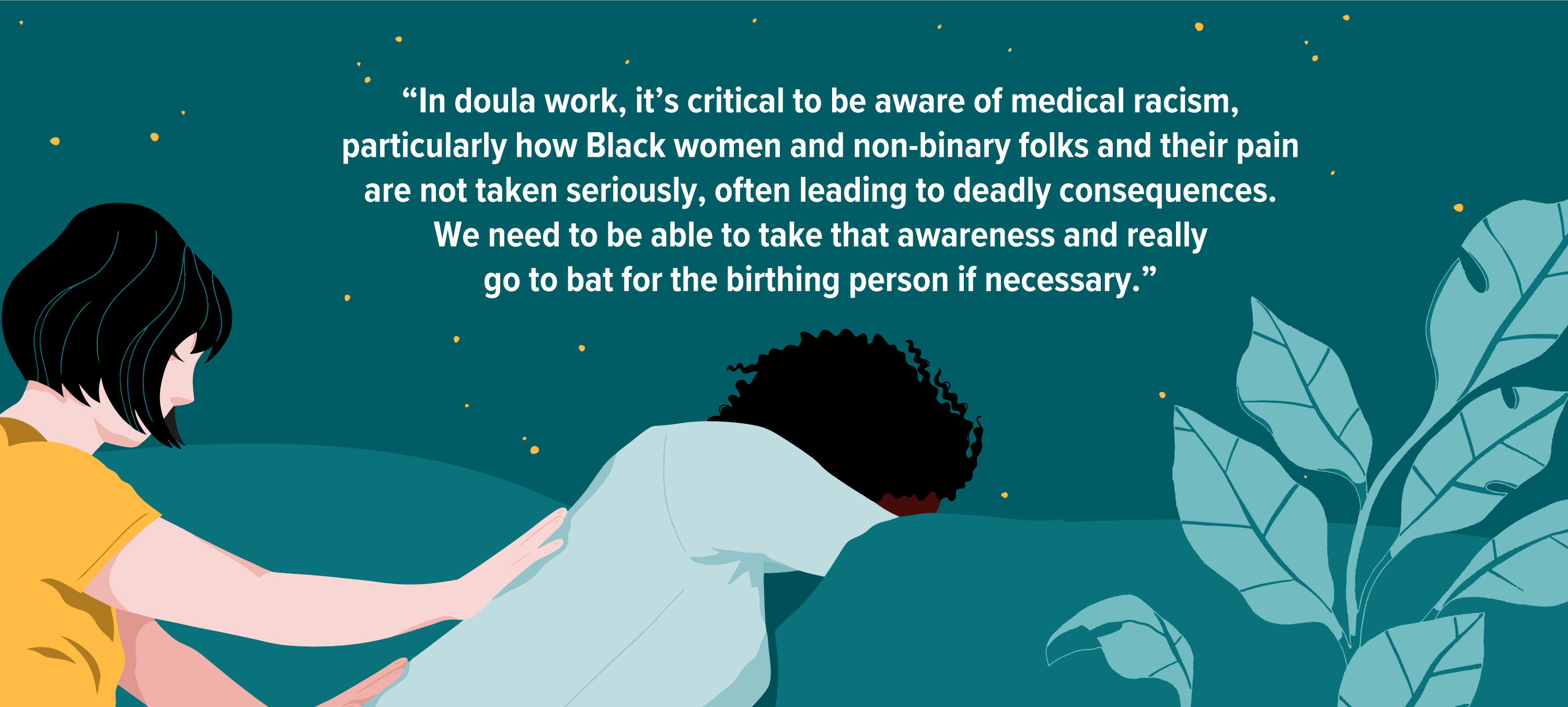

Doulas are valuable maternal allies

Katya Weiss-Andersson, an anti-racist doula and queer activist, explains that her role as a doula helps expectant mothers navigate not only pregnancy, but pushback from physicians.

In some cases, mothers even turn to home births for this reason. “Our job is to fully respect and advocate for the birthing person’s choices rather than imposing our own ideas onto them,” she shares.

“In my experience, I have seen home births significantly circumvent a lot of these disempowering, dehumanizing experiences, but home births are not feasible or desirable to every birthing parent, and it isn’t our job to persuade anyone to birth in a certain way. We need to be able to act as advocates in true solidarity whether in a home birth, birth center, or hospital environment.”

“In doula work, it’s critical to be aware of medical racism, [particularly how] Black women and nonbinary folks and their pain are not taken seriously, often leading to deadly consequences. We need to be able to take that awareness and really go to bat for the birthing person if necessary,” Weiss-Andersson explains about her role as a doula.

“[Mothers] are in the midst of birthing an entire child, so if they are not being respected or taken seriously, our job as their doula is to be their advocate [as] an extension of their agency and bodily autonomy.”

Illustrations by Alyssa Kiefer

The American employment system fails Black mothers

Beyond the emotional aspects that affect instinct, intuition, and trust, systemic racism continues to rear its head. Black women already face a significant pay gap, and when you compound that with pregnancy, the American employment system fails Black mothers even further.

If Black mothers cannot take time off — whether due to their job itself, due to finances, or both — they are more likely to miss appointments and/or not be able to schedule impromptu appointments when something seems wrong.

“[Due to my understanding employer], my paid sick time was not eaten up by my doctor’s appointments,” Anne recalls in regard to the birth of her third child. “But for many women, that’s not the case.”

Pair that with an ineffective healthcare system that fails a multitude of Americans, and there you have it: increasingly more variables that make Black maternal health statistics so grim.

Steps can the U.S. take to improve the state of Black maternal health

Luckily, there are organizations trying to improve the outlook of Black maternal health and decrease mortality rates.

Black Mamas Matter Alliance states that they are “a national network of Black women-led organizations and multi-disciplinary professionals who work to ensure that all Black Mamas have the rights, respect, and resources to thrive before, during, and after pregnancy.”

This collective consists of medical doctors, PhDs, doulas, wellness centers, and justice organizations that advocate for the lives of all “Black Mamas”—and not just ones that are cisgender.

Likewise, there are ample physicians trying to unlearn their biases and provide better patient care on a personal level. Such is the case with Dr. Tanouye.

“Personally, I continue to work on this daily,” she explains. “I work to ensure that my patients feel heard, that they understand me, and that they feel that we are a team working together to achieve their best health. I strongly believe in choice and mutual decision-making that is unique to each patient. My role is to validate their concerns by listening and offering a thorough evaluation, and then help guide them to safe solutions.”

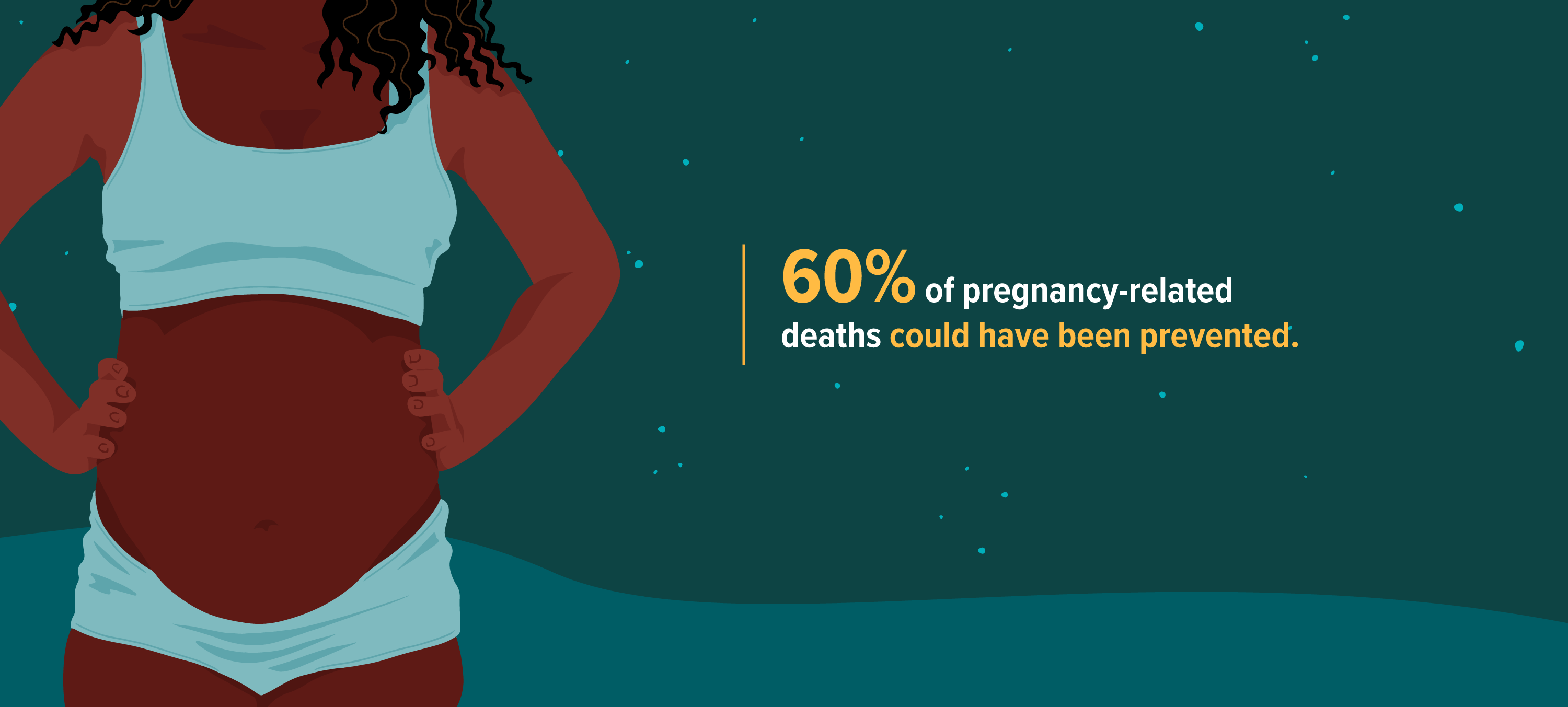

Most pregnancy-related deaths could have been prevented

For women who feel like they aren’t being heard, Dr. Tanouye advises the importance of assessing the environment and asking oneself key questions. Namely, “How comfortable a patient feels when a provider is addressing their concerns. Are their questions being answered with compassion, are physical concerns being evaluated and taken seriously, and does the patient feel heard and understood?” If the aforementioned signs point to invalidation, it’s time to move on.

Therein lies the crux of the issue: validation. In a society built on systemic racism, Black voices have never been amplified and Black lives fail to be validated.

Shalon Irving. Sha-asia Washington. Amber Rose Isaac.

These are just a few of the names that deserve to be remembered as we illuminate the injustices of pregnancy-related deaths,

Illustrations by Alyssa Kiefer

Shalon Irving. Sha-asia Washington. Amber Rose Isaac.

Black mothers matter

The critical and non-negotiable need to validate and protect Black lives is a public health issue, and one being addressed by Black Lives Matter in an effort to battle a different angle of systemic racism in America: police brutality.

#BlackLivesMatter dates back to 2013, an initiative created in response to Trayvon Martin and the subsequent acquittal of his murderer. Now, 7 years later, the unjustifiable violence against Black lives has passionately galvanized a larger audience than ever before.

Black Lives Matter is currently at the forefront of conversations not only across the United States, but across the globe. The movement, which is headed up by an organization operating in the United States, U.K., and Canada, has the mission of “[eradicating] white supremacy and [building] local power to intervene in violence inflicted on Black communities by the state and vigilantes.”

It’s safe to say that the neglect of Black women in hospitals and examination rooms across the country is a form of racially motivated violence, too. Police officers are sworn to protect and serve, just as physicians are sworn to the Hippocratic Oath. But when all is said and done, a promise made is not a promise kept.

Black women, much like they’ve had to do throughout the course of American history, must advocate for themselves and their health — even though advocacy shouldn’t be the difference between life and death.

“Always follow your gut,” says Dr. Tanouye. “Don’t ignore it and don’t let anyone else brush it off.”