Ask someone what they think about the idea of “Medicare for All” — that is, one national health insurance plan for all Americans — and you’ll likely hear one of two opinions: One, that it sounds great and could potentially fix the country’s broken healthcare system. Or two, that it would be the downfall of our country’s (broken) healthcare system.

What you likely won’t hear? A succinct, fact-based explanation of what Medicare for All would actually entail and how it could affect you.

It’s a topic that is especially relevant right now. In the midst of the 2020 U.S. presidential election, Medicare for All has become a key point of contention in the Democratic Party primary. From Senators Bernie Sanders and Elizabeth Warren’s embrace of single-payer healthcare to former Vice President Joe Biden and Sen. Amy Klobuchar’s embrace of reforms to the Affordable Care Act (ACA), how to best improve healthcare in America is a divisive issue for voters.

It also can become confusing and difficult to parse out differences between different policies in order to assess how they might impact your day-to-day life if enacted. The other question in this divisive political climate: Will any of these plans be enacted in a Washington D.C. that has been defined more by its partisan divides and policy inaction?

To try to make sense of Medicare for All and how the politics of the day are impacting America’s approach to health coverage, we asked healthcare experts to answer your most pressing questions.

What is the overall plan?

One of the biggest misconceptions about Medicare for All is that there’s just one proposal on the table.

“In fact, there are a number of different proposals out there,” explained Katie Keith, JD, MPH, a research faculty member for Georgetown University’s Center on Health Insurance Reforms.

“Most people tend to think of the most far-reaching Medicare for All proposals, which are outlined in bills sponsored by Sen. Bernie Sanders and Rep. Pramila Jayapal. But there are a number of proposals out there that would expand the role of public programs in healthcare,” she said.

Although all of these plans tend to get grouped together, “there are key differences among the various options,” Keith added, “and, as we know in healthcare, the differences and details really matter.”

According to the Kaiser Family Foundation, Sanders’ and Jayapal’s bills (S. 1129 and H.R. 1384, respectively) share many similarities, such as:

- comprehensive benefits

- tax financed

- a replacement for all private health insurance, as well as the current Medicare program

- lifetime enrollment

- no premiums

- all state-licensed, certified providers who meet eligible standards can apply

Other bills put a slightly different spin on single-payer health insurance. For instance, they may give you the right to opt out of the plan, offer this healthcare only to people who don’t qualify for Medicaid, or make it eligible to people who are only between the ages of 50 and 64.

When it comes to the current Democratic presidential primary, out of a field that initially numbered nearly 30 candidates, support for Medicare for All offered something of a litmus test for who would be considered a “progressive” along the lines of Sanders and who would fall more on the side of building upon the existing system put forward by the Obama administration.

Out of the remaining candidates in the Democratic field, Warren is the only top-tier contender who embraces a full-on implementation of a Medicare for All Plan over the course of a hypothetical first term. Outside of that top tier, Rep. Tulsi Gabbard, Congresswoman from Hawaii, also embraces a Medicare for All approach.

Warren’s plan essentially has the same objectives of Sanders’ bill. She’s advocated for phasing in this system. In the first 100 days of her presidency, she would use executive powers to reign in high insurance and prescription drug costs while also introducing a pathway for people to opt in for a government Medicare system if they choose. She says that by the end of her third year in office, she would advocate to pass legislation for a full national transition to a Medicare for All system, according to the Warren campaign website.

So far this election cycle, there has been contention over how these plans would be implemented. For instance, other top candidates might not advocate for a stringent Medicare for All policy like that promoted by Warren and Sanders. Instead, the focus of this other group of candidates is building upon and expanding coverage provided by the ACA.

Former South Bend, Indiana, Mayor Pete Buttigieg has advocated for what his campaign calls “Medicare for All who want it,” adding a public option to the ACA. This means a government-supported public Medicare option would exist alongside the choice of keeping one’s private health plan, according to the candidate’s website.

The other top candidates support possibly working toward this goal. Biden is campaigning on improving upon the ACA with the potential goal of a public option down the line. This incrementalist approach is also shared by Minnesota Sen. Amy Klobuchar and former New York City mayor Michael Bloomberg.

John McDonough, DrPH, MPA, a professor of public health practice in the department of health policy and management at the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health and director of executive and continuing professional education, said since Medicare for All discussions have been framed as a “for or against debate” by media analysts and political handicappers this cycle, the atmosphere has become particularly contentious.

It’s something McDonough is certainly familiar with, given he previously worked on the development and passage of the ACA as a senior advisor on national health reform to the U.S. Senate Committee on Health, Education, Labor, and Pensions.

“The other issues on the table in the Democratic debates do not parse so easily, and that helps to explain the prominence of this issue tied to the overall interest in health system reform,” he told Healthline.

Sources: https://www.kff.org/uninsured/fact-sheet/key-facts-about-the-uninsured-population/

How, exactly, would Medicare for All work?

As far as the current legislation on the table like the Sanders and Jayapal bills, “the simplest explanation is that these bills would move the United States from our current multi-payer healthcare system to what is known as a single-payer system,” explained Keith.

Right now, multiple groups pay for healthcare. That includes private health insurance companies, employers, and the government, through programs like Medicare and Medicaid.

Single-payer is an umbrella term for multiple approaches. In essence, single-payer means your taxes would cover health expenses for the whole population, according to a definition of the term from the

Right now in the United States, multiple groups pay for healthcare. That includes private health insurance companies, employers, and the government, through programs like Medicare and Medicaid.

The system we have right now places America’s health system on an island on its own, away from its peers on the global stage.

For instance, the Commonwealth Fund reports the United States ranks last “on measures of quality, efficiency, access to care, equity, and the ability to lead long, healthy, and productive lives.” This is compared to six other major industrialized countries — Australia, Canada, Germany, the Netherlands, New Zealand, and the United Kingdom. Another dubious honor for the United States? The system here is by far the most expensive.

“Under Medicare for All, we would have only a single entity — in this case, the federal government — paying for healthcare,” said Keith. “This would largely eliminate the role of private health insurance companies and employers in providing health insurance and paying for healthcare.”

The current Medicare program wouldn’t exactly vanish.

“It would be also expanded to cover everyone and would include much more robust benefits (such as long-term care) that [are] not currently covered by Medicare right now,” said Keith.

What might out-of-pocket costs look like for different income brackets?

Despite what some online conspiracy theories warn, “under the Sanders and Jayapal bills, there would be virtually no out-of-pocket costs for healthcare-related expenses,” Keith said. “The bills would prohibit deductibles, coinsurance, co-pays, and surprise medical bills for healthcare services and items covered under Medicare for All.”

You may have to pay some out-of-pocket costs for services that aren’t covered by the program, “but the benefits are expansive, so it’s not clear that this would happen often,” said Keith.

The Jayapal bill fully prohibits all cost-sharing. The Sanders bill allows for very limited out-of-pocket costs of up to $200 per year for prescription drugs, but that doesn’t apply to individuals or families with an income under 200 percent of the federal poverty level.

Other proposals, such as the Medicare for America Act from Reps. Rosa DeLauro (D-Conn.) and Jan Schakowsky (D-Ill.), would nix out-of-pocket costs for lower-income individuals, but people in higher income brackets would pay more: up to $3,500 in annual out-of-pocket costs for individuals or $5,000 for a family.

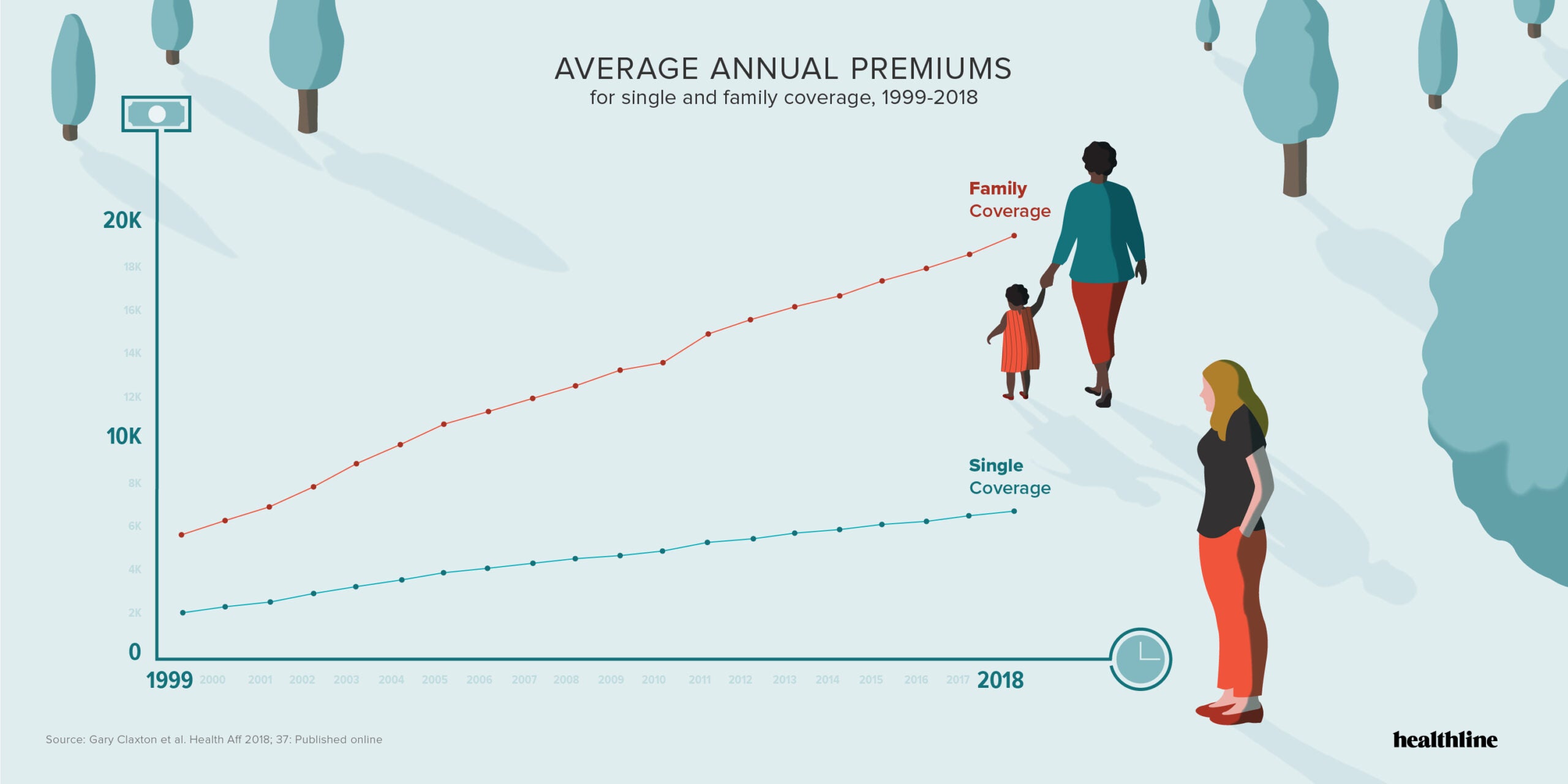

Source: Gary Claxton et al. Health Aff 2018; 37: Published online

Will you be able to keep your doctor?

This is a sticking point for many people — and why not? It can take time to find a doctor you trust, and once you do, you don’t want to walk away from that relationship.

The good news is that “the Medicare for All bills generally build on the current provider system, so doctors and hospitals that already accept Medicare could likely continue to do so,” Keith said.

What isn’t clear yet is whether all providers would choose to participate in the program since they currently won’t be required to do so.

“The bills include a ‘private pay’ option where providers and individuals could come up with their own arrangement to pay for healthcare, but this would be outside of the Medicare for All program, and they would have to follow certain requirements before doing so,” explained Keith.

Will private insurance still be available?

Neither Sanders and Jayapal bills, nor proposals like Warren’s, would allow private health insurance to operate the way it does now.

In fact, the current Sanders and Jayapal bills “would prohibit employers and insurance companies from offering insurance that covers the same benefits that would be provided under the Medicare for All program,” Keith said. “In other words, insurers couldn’t offer coverage that would duplicate the benefits and services of Medicare for All.”

Considering that in 2018, the average cost for employer-based family healthcare was up 5 percent to nearly $20,000 per year, maybe that’s not a bad thing.

The number of Americans without health insurance also increased in 2018 to 27.5 million people, according to a report issued in September by the U.S. Census Bureau. This is the first increase in uninsured people since the ACA took effect in 2013.

A Medicare for All option could provide coverage for a significant number of those who are currently unable to afford healthcare under the current system.

Through his “Medicare for All who want it” proposal, Buttigieg says the coexistence of a public option along with private insurers would force big insurance companies to “compete on price and bring down costs.”

This has generated questions from critics of Buttigieg’s approach, who say allowing the current insurance industry to function much as it has before, not much “reform” is actually taking place. Former insurance executive-turned-Medicare for All-advocate Wendell Potter recently examined this on a popular Twitter thread, writing: “This will thrill my old pals in the insurance industry, as Pete’s plan preserves the very system that makes them huge profits while bankrupting & killing millions.”

Will preexisting conditions be covered?

Yes. Under the Affordable Care Act, a health insurer can’t refuse to give you coverage because of a health issue you already have. That includes cancer, diabetes, asthma, and even high blood pressure.

Before the ACA, private insurers were allowed to turn down prospective members, charge higher premiums, or limit benefits based on your health history.

Medicare for All plans will operate in the same way as the ACA.

Will Medicare for All solve all the problems of our healthcare system?

“The honest, although somewhat dissatisfying answer at this stage is ‘It depends,’” said Keith.

“This would be a brand new, very ambitious program that would require a lot of changes in the way healthcare is paid for in the United States. There are likely to be at least some unintended consequences and other costs in the form of higher taxes, at least for some people,” she said.

But if the bills work as well in real life as they look on paper? “People would be insulated from out-of-pocket costs like high prescription costs and surprise hospital bills,” Keith said.

Let’s say Medicare for All happens. How would the transition occur?

That depends on how disruptive of a model is adopted, said Alan Weil, JD, MPP, editor-in-chief of Health Affairs, a journal of health policy thought and research.

“If we literally eliminate all private insurance and give everyone a Medicare card, it would probably be implemented by age groups,” Weil said.

People would have a few years to transition, and once it’s your turn, “you’d move from private coverage and into this plan,” Weil said. “Because the vast majority of providers take Medicare now, conceptually, it’s not that complicated.”

Although the current Medicare program truly is. While it covers basic costs, many people still pay extra for Medicare Advantage, which is similar to a private health insurance plan.

If legislators decide to keep that around, open enrollment will be necessary.

“You’re not just being mailed a card, but you could also have a choice of five plans,” said Weil. “Preserve that option and that offers a layer of complexity.”

Architects of a single-payer health system will also have to tweak Medicare to make it suitable for people who aren’t only 65 or over.

“You’d have to come up with billing codes and payment rates and enroll a bunch of pediatricians and providers who aren’t currently involved with Medicare,” Weil noted. “There’s a lot that would need to happen behind the scenes.”

Katie Keith, JD, MPH

How will Medicare for All be financed?

The specifics vary a bit plan to plan. In Jayapal’s bill, for instance, Medicare for All would be funded by the federal government, using money that otherwise would go to Medicare, Medicaid, and other federal programs that pay for health services.

But when you get right down to it, the funding for all the plans comes down to taxes.

That still might not be as awful as it sounds.

After all, “you won’t be paying [health insurance] premiums,” Weil pointed out.

Although you may be able to say right now that your employer pays part of your health benefits, “economists would say it comes out of your pocket,” Weil said. “You’re also paying office co-pays and deductibles.”

With Medicare for All proposals, some portion of the money you’re now paying toward health insurance would be shifted to taxes.

Will quality of care go down?

“The rhetorical response to single-payer health insurance is that it’s government-controlled healthcare. It’s then used to argue that the government would be making important decisions about the care you get and don’t get, and who you see,” Weil said.

But Medicare for All could actually give you more choice than private insurance.

“With Medicare, you can go to any doctor,” Weil said. “I have private insurance and have a lot more restrictions as to who I see.”

How likely is it that Medicare for All will happen?

Likely, but not any time soon, guesses Weil.

“I think we’re divided politically in lots of ways as a country,” he explained. “I don’t see our political process able to metabolize change on this scale.”

Plus, healthcare providers, legislators, policy makers, and insurance providers are still trying to wrap their heads around what this change would mean.

On the other side of optimism, McDonough stresses that Medicare for All would have to accomplish what looks like a Herculean task in today’s world — pass a divided U.S. Congress.

From his perspective, McDonough said “financially and administratively, Medicare for All could be achieved, recognizing some significant disruption and confusion as a certainty.”

Looking at the current roadmap to healthcare reform of any kind, McDonough said unless the Democrats control the Senate with at least 60 votes, “Medicare for All would not be achievable in 2021, even with a President Sanders.”

“Right now, according to nonpartisan polling, the odds of Democrats retaining a majority in the U.S. Senate is less than 50 percent,” he added.

When citizens are polled on the subject, they agree that the concept of Medicare for All sounds good, said Weil. “But when you start to talk about disruption in coverage and the potential of taxes to go up, people’s support starts to weaken,” he said.

A Kaiser Family Foundation tracking poll published in November 2019 shows public perception of Medicare for All shifts depending on what detail they hear. For instance 53 percent of adults overall support Medicare for All and 65 percent support a public option. Among Democrats, specifically, 88 percent support a public option while 77 percent want full-scale Medicare for All. When looked at a little more closely, attitudes about health reform get more complicated.

When Medicare for All is described as requiring more taxes, but still eliminating out-of-pocket costs and premiums, favorability drops below half to 48 percent of adults overall. It also drops to 47 percent when described as a tax raise but a decrease in overall healthcare costs. Although there’s a growing sense that our current healthcare system isn’t sustainable, “you learn to navigate what you have,” Weil added.

In other words, you may despise your health insurance, but at least you understand just how awful it is.

Weil thinks it’s likely that “elements of pressure” will start making the debate about Medicare for All less relevant. Healthcare systems will continue merging and buying up acute care centers, for instance. Prices will keep rising.

Public outrage may force the government to step in and regulate the healthcare system over time.

“And once you have a consolidated, regulated industry, it’s not that different than single-payer,” he pointed out.

And it might not be as different as you feared — and much better for your health (and your wallet) — than you hoped.

Additional reporting by Brian Mastroianni